ROBINSON CRUSOE: a possible route of his epic 1688 winter crossing of the Pyrenees mountains, in which took place his battle with 300 ravenous wolves

An appreciation of Robinson Crusoe dans les Pyrénées (1995), a book by Joseph RIBAS

Robinson Crusoe dans les Pyrénées was published in France by Éditions Loubatières (ISBN: 2-86266-235-6). The copyright (and all other rights) relating to this book are now held by Joseph Ribas (b. 1931).

Joseph Ribas's book is based upon chapters 19 and 20 of "Robinson Crusoe" (1719) by Daniel Defoe. The text of those chapters is available as an annex to this website (in pdf format).

Joseph Ribas's book itself contains text extracts from the 1836 French version of Defoe's "Robinson Crusoe", by Pétrus Borel.

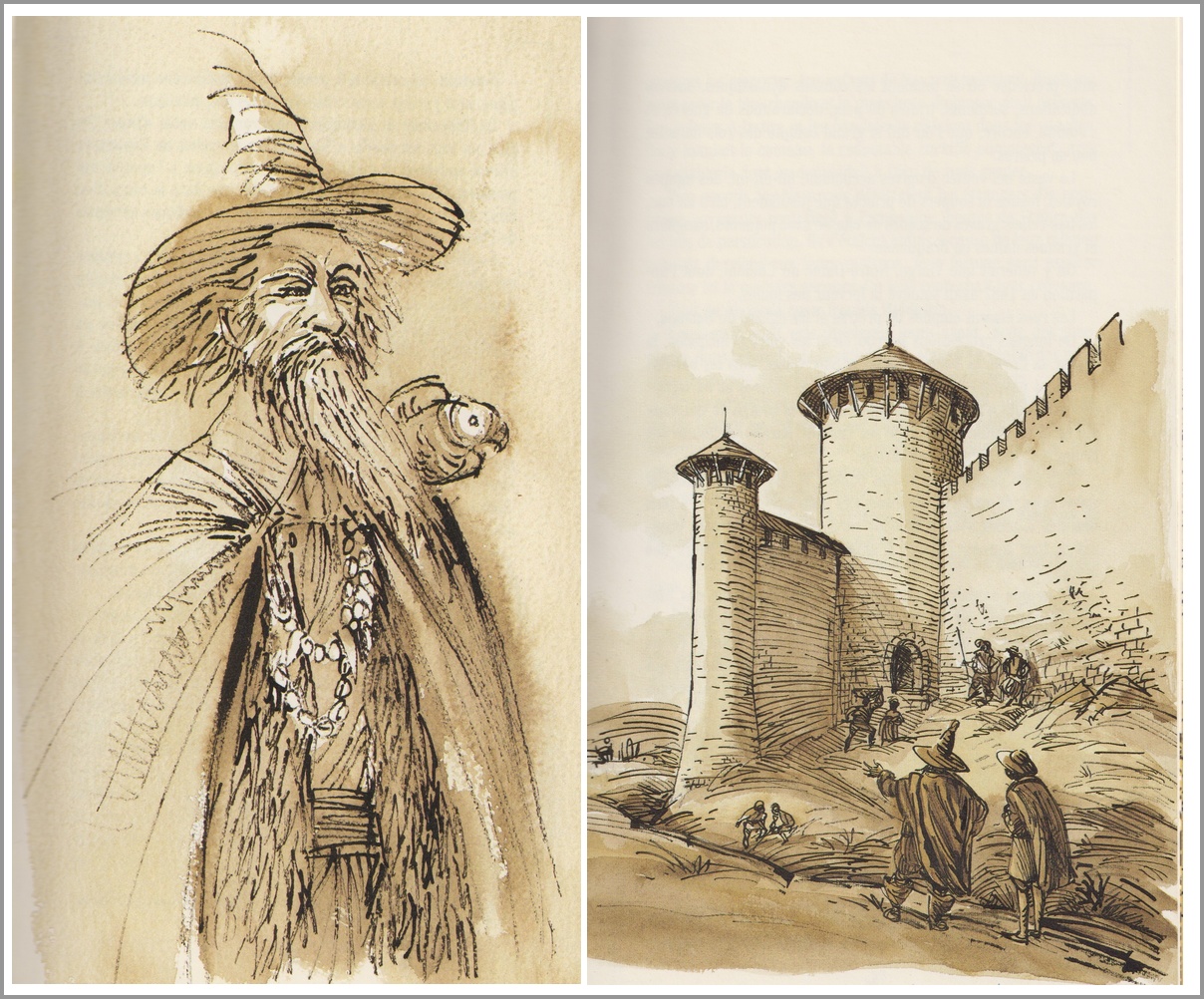

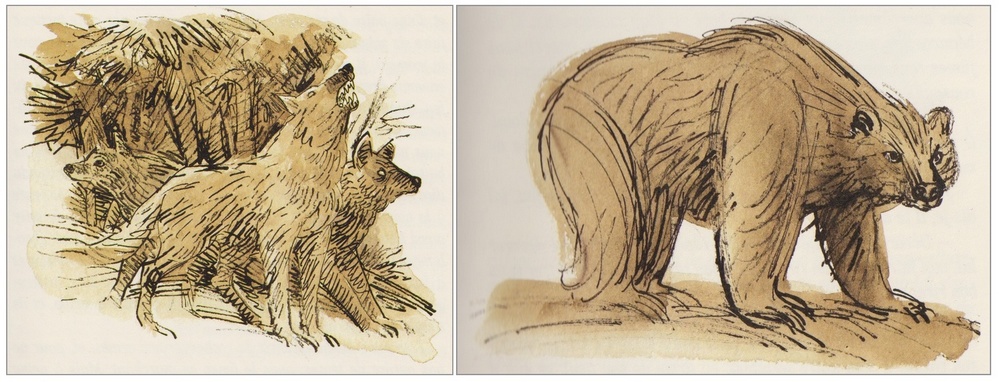

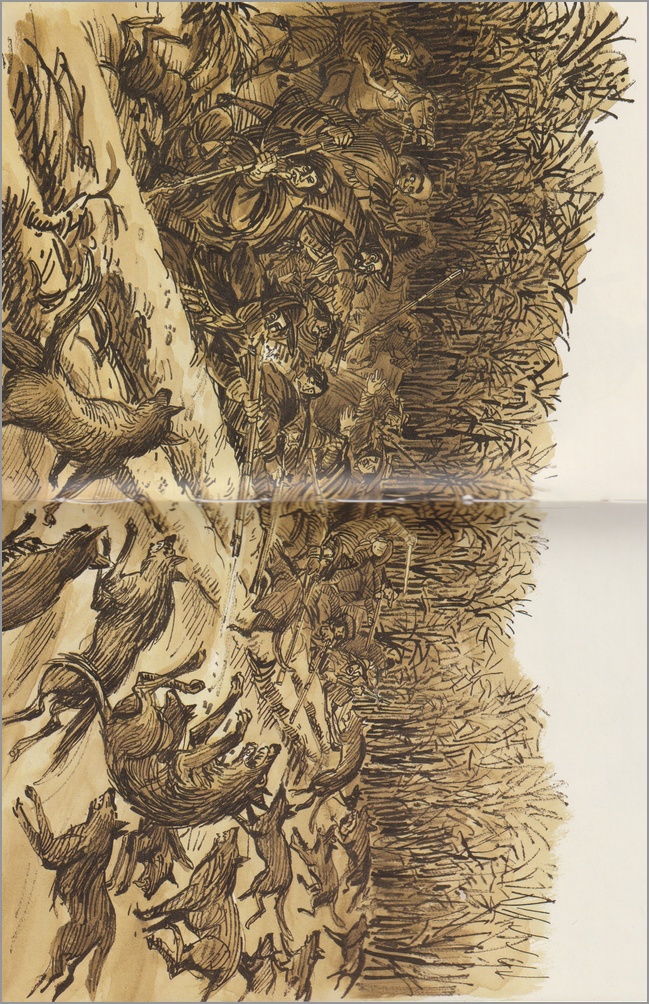

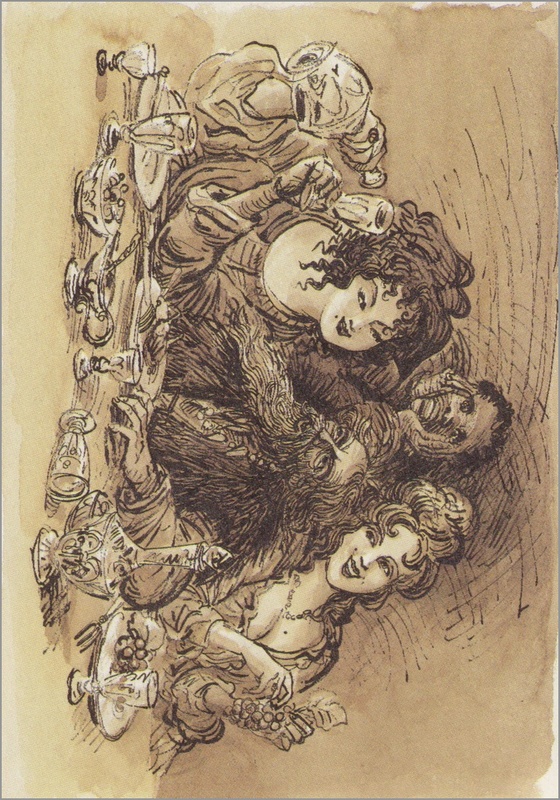

The illustrations in Joseph Ribas's book were by Jean-Claude Pertuzé (1949-2020). Those illustrations include the one on the book cover (above), and others reproduced below.

This website, which is non-commercial and non-profit-making, was prepared on a personal basis by Alan Mattingly.

*******************************************

All the world knows the story of Robinson Crusoe.

At least, it knows the main part of the tale, in outline: a man is shipwrecked; he finds himself alone on a remote island; he manages to survive there for many years, despite hardship and solitude; eventually he encounters other human beings; and after more adventures he returns home, to England.

But what the world, or most of it, probably does not know is that the novel by Daniel Defoe (1660 - 1731), first published in London in 1719, does not end there. The final two chapters (numbers 19 and 20) mostly concern a further, and in part quite terrifying, experience which Crusoe endured when he and a group of about 30 companions made a crossing on horseback of the central Pyrenees mountains, from Spain to France, in the fearsome winter of late 1688.

The principal event in this journey occurs a few days after Crusoe and his group have crossed the Spanish-French frontier on the spine of the Pyrenees and are descending northwards in France through forests in the foothills of the mountains. They are attacked by no fewer than 300 ferocious wolves. The travellers are horrified. But they are well-armed, and, under Crusoe’s leadership, they manage to kill many of the wolves and scare the others away.

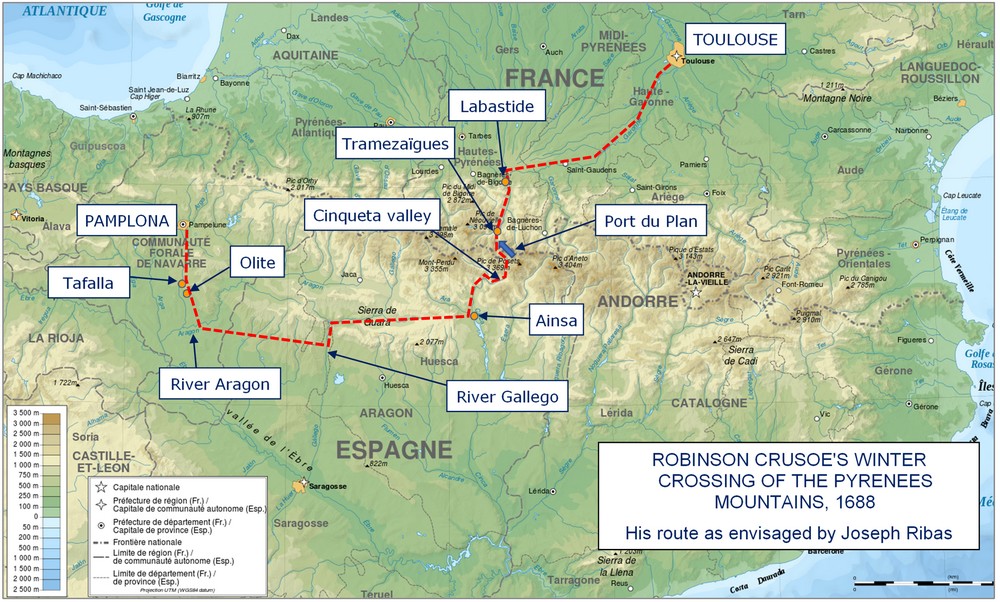

In Defoe’s novel, we are told that the party sets out from Pamplona, Spain in November 1688. They eventually arrive in Toulouse (France), perhaps about three weeks later. (From there, Crusoe has an uneventful journey to Paris, then Calais, and he lands "safe at Dover the 14th of January" (1689).)

However, although Defoe’s description of Crusoe’s route over the Pyrenees reads as if he had a specific itinerary in mind, he cites very few actual geographical locations. The details of the route which he gives in the story leave much to the imagination.

So an intriguing question arises: is it possible to define a route which can actually be traced on the ground and which is also consistent with the description of the crossing that is given in the novel?

The answer is 'Yes'. Joseph Ribas puts forward such a route in his book Robinson Crusoe dans les Pyrénées. Joseph Ribas is a French author who has been writing about the Pyrenees mountains for decades and whose knowledge of these mountains is second to none. His justification for the route which he describes is persuasive.

Moreover, a route similar to that suggested by Joseph Ribas had also been put forward some 80 years earlier by another writer, Léopold Médan, whose work ("Une Traversée des Pyrénées Centrales à la fin de XVIIe siècle - Robinson Crusoé en Gascogne", Léopold Médan, Revue de Gascogne, tome X, septembre-octobre 1910) is cited in Joseph Ribas's book.

The route proposed by Joseph Ribas is outlined below. But, first, what took Crusoe to Spain, and why did he want to cross the mountains into France, in the winter?

Why Crusoe went to Pamplona

Crusoe returns to England after his famous adventures as a castaway "on the 11th of June, in the year 1687, having been thirty-five years absent". But he soon finds that he is not very happy there, not least because he believes he has little money.

He decides to travel, by sea, to Lisbon, where he has business interests. As ever, he is accompanied by his "man Friday". Not long after arriving in Lisbon, in April 1688, he finds that he is in fact a wealthy man. He decides to have his wealth transferred to England and to return there himself.

But he is reluctant to return by sea. Some instinct tells him that such a journey would not end well. Finally, afer spending "some months" in Lisbon, he decides to return to England by land. He gathers around him some travelling companions and he sets off for Madrid. He is there in "the latter part of the summer".

In "about the middle of October" Crusoe leaves Madrid. The weather is still hot. He and his party head north towards Pamplona. He seems to assume that, from there, it will be a straightforward affair to continue north, over the western Pyrenees, and into France.

But by the time the group reaches Pamplona, "but ten days out of Old Castile", winter has arrived - and with a vengance. The cold is "insufferable". Heavy snow has fallen and continues to fall. Crossing the mountains immediately north of Pamplona has become impossible.

Stuck in Pamplona, Crusoe then meets "four French gentlemen" who had lately succeeded in crossing the mountains from France. They had been led by a guide who brought them over from Languedoc (that is, from somewhere considerably further to the east, Languedoc then being a province of France which lay, roughly speaking, to the south and east of Toulouse). The French gentlemen and their guide had crossed the mountains "by such ways that they were not much incommoded with the snow".

Crusoe sends for this guide and engages the man to lead his party the same way, in the opposite direction.

More travellers join Crusoe's group and they leave Pamplona on "the 15th of November" (1688). They number more than 30, and they are "very well mounted and armed".

The journey across northern Spain

At first, and to Crusoe's surprise, the guide leads the party southwards, back in the direction of Madrid, "about twenty miles". Joseph Ribas suggests that this would have taken them to Tafalla, from where they would have turned off the Madrid road and headed to Olite. At the auberge there, Joseph Ribas has Crusoe being assured by his hosts that his journey ahead, although long, should be feasible.

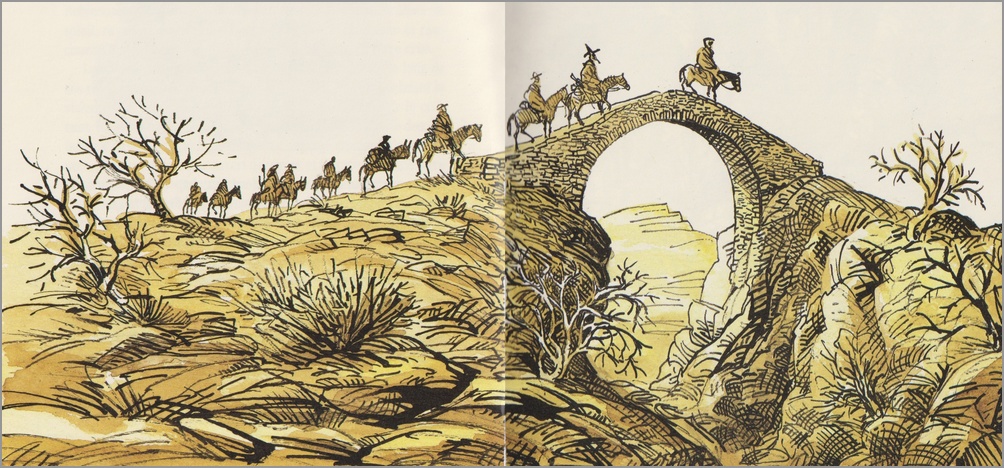

Defoe tells us that the travellers then find themselves in "the plain country", in "a warm climate again, where the country was pleasant". They pass "two rivers". Consistent with this, Joseph Ribas has them travelling in a broadly eastward direction, parallel to the chain of Pyrenees mountains, but well to the south of those mountains. They would have crossed several rivers, but traversing two major ones in particular - the rivers Aragon and Gallego - could have called for some care and could well have made a mark on Crusoe's memory. Joseph Ribas then has Crusoe and his companions continuing their eastward journey through Aragon by going north of the Sierra de Guarra range of hills.

Then, "on a sudden turning to his left", the guide approaches the mountains. Based on this, Joseph Ribas has Crusoe and his companions move northwards up the Cinca valley. They pass Ainsa, on the Cinca river, in the foothills of the mountains. Further north, Joseph Ribas has them turn right and go up the Cinqueta valley.

By now, the travellers are surrounded by "hills and precipices" which, to Crusoe, look "dreadful". Joseph Ribas suggests that this description could correspond to the huge, abrupt limestone slopes which rise up from the valley bottom in this area.

Higher up, towards the frontier, the landscape becomes more rounded. Here, the ancient crossing route used by traders, shepherds and other travellers climbed steadily in zig-zags towards the head of the valley. And indeed, it is here that, on ascending steadily, Crusoe remarks that his guide makes "so many tours... meanders... and... winding ways" that the group "insensibly" arrives at the "height of the mountains without being much encumbered by the snow".

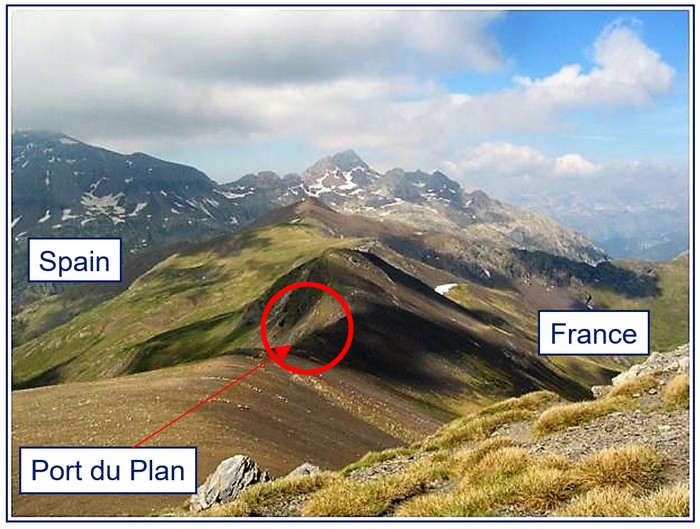

The descent into France from the Port du Plan

Image: cirquedebarrosa.free.fr

Joseph Ribas suggests that this crossing point could be a place on the frontier between France and Spain called the Port du Plan. ("Port" is a term used in the Pyrenees for a col, or pass, in the mountains. "Plan" is the name of a village in the Pyrenees mountains not far south of the Port du Plan.) It is a broad and relatively unintimidating pass on the crest of the Pyrenees, with land rising relatively gently on either side. It lies at an altitude of about 2500 metres. As mentioned just now, it was used by a very old route over the mountains between France and Spain.

"On a sudden," as Crusoe says, the guide then points out land lying far to the north - "the pleasant and fruitful provinces of Languedoc and Gascony" (Gascony is a part of France which lies to the west of Languedoc and extends north from the high Pyrenees, to lowland country west of Toulouse), "all green and flourishing". This again is consistent with the travellers being at the Port du Plan.

Moreover, as Joseph Ribas writes, "of all the crossing points in this part of the Pyrenees, the Port du Plan was the most accessible and offered the most direct route to reach the nearest village on the French side." So it would have been a good choice to make, provided, as was the case in the novel, that snow conditions were not prohibitive.

The next few days of Crusoe's journey - the descent northwards into France - is described in only a brief paragraph in Defoe's novel. After being delayed by a snowstorm, the travellers "began to descend every day, and to come more north than before; and so, depending on our guide, we went on."

Joseph Ribas has Crusoe and his followers descending and moving "more north" by going down the Rioumajou valley (immediately below the Port du Plan), past Tramezaïgues, and from there, approximately northwards still, down the Aure valley.

The wolves attack

Then, somewhere beyond the high mountains, but still in a country of forests where some snow lay, the central events of "Crusoe in the Pyrenees" take place. Some "three leagues" (about 15 kilometres) before a village where the travellers are to lodge for the night, the guide, ahead of the others, is attacked by wolves. Friday saves his life, but the guide is seriously wounded.

The travellers move on. After further episodes (including one involving a bear in a tree), but still in the same evening, more wolves are encountered. This culminates in the battle with 300 wolves, which Crusoe and his friends only survive by the skin of their teeth.

"...This filled us with horror, and we knew not what course to take; but the creatures resolved us soon, for they gathered about us presently, in hopes of prey; and I verily believe there were three hundred of them. I drew my little troop in among those trees, and placing ourselves in a line behind one long tree, I advised them all to alight, and keeping that tree before us for a breastwork, to stand in a triangle, or three fronts, enclosing our horses in the centre. We did so, and it was well we did; for never was a more furious charge than the creatures made upon us in this place. They came on with a growling kind of noise, and mounted the piece of timber, which, as I said, was our breastwork, as if they were only rushing upon their prey; and this fury of theirs, it seems, was principally occasioned by their seeing our horses behind us. I ordered our men to fire as before, every other man; and they took their aim so sure that they killed several of the wolves at the first volley; but there was a necessity to keep a continual firing, for they came on like devils, those behind pushing on those before.

"When we had fired a second volley of our fuses, we thought they stopped a little, and I hoped they would have gone off, but it was but a moment, for others came forward again; so we fired two volleys of our pistols; and I believe in these four firings we had killed seventeen or eighteen of them, and lamed twice as many, yet they came on again. I was loath to spend our shot too hastily; so I called my servant, not my man Friday, for he was better employed, for, with the greatest dexterity imaginable, he had charged my fuse and his own while we were engaged - but, as I said, I called my other man, and giving him a horn of powder, I had him lay a train all along the piece of timber, and let it be a large train. He did so, and had but just time to get away, when the wolves came up to it, and some got upon it, when I, snapping an unchanged pistol close to the powder, set it on fire; those that were upon the timber were scorched with it, and six or seven of them fell; or rather jumped in among us with the force and fright of the fire; we despatched these in an instant, and the rest were so frightened with the light, which the night - for it was now very near dark - made more terrible that they drew back a little; upon which I ordered our last pistols to be fired off in one volley, and after that we gave a shout; upon this the wolves turned tail, and we sallied immediately upon near twenty lame ones that we found struggling on the ground, and fell to cutting them with our swords, which answered our expectation, for the crying and howling they made was better understood by their fellows; so that they all fled and left us."

Crusoe and his followers then make their escape. By the time arrive in the village, night has fallen. The villagers, frightened and armed, have lately themselves been fighting off bears and wolves, who have come right into the village seeking something to devour.

Joseph Ribas suggests that this village could correspond to a small settlement called Labastide. It is at the northern end of the foothills of the Pyrenees, in the lower Aure valley. It lies at an altitude of about 550m. There is higher ground, rising to over 1200 metres, immediately to the south. Joseph Ribas points out that hungry and desperate animals could have entered this village because, by contrast with its neighbour Labarthe-de-Neste, Labastide had no walls to protect it.

The settlement of Labastide in the Hautes-Pyrénées département of France, as it is today.

Image: Wikimedia Commons

But, after this village, Crusoe has nothing to say about the final stage of his journey, which was across what is essentially lowland country. This stage was to Toulouse, which lies over 100 kilometres to the north-east of Labastide. All Crusoe is pleased to say is that, there, "we found a warm climate, a fruitful, pleasant country and no snow, no wolves, nor anything like them."

As mentioned earlier, Crusoe then travels north across France, and crosses the Channel to arrive in England in January 1689.

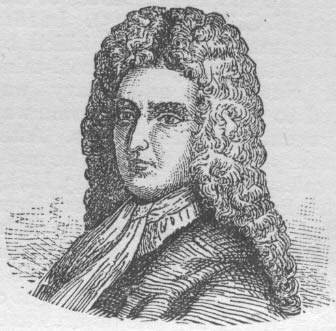

Did Daniel Defoe cross the Pyrennes?

Daniel Defoe

This then is the route which Joseph Ribas suggests that Crusoe and his party could have followed between Pamplona and Toulouse. Did Daniel Defoe have in mind this route when he wrote Chapters 19 and 20 of "Robinson Crusoe"? If so, did he hear about it from traders or other travellers who he met at some time in his life before he wrote "Robinson Crusoe"? Did he read about it somewhere, or see it marked on a map which he believed to be reliable? Did he even follow that route himself at some time, and base the account in the novel on his memory of that journey?

It seems that no-one has definite answers to these questions.

Joseph Ribas would dearly like to believe that Defoe travelled in the Pyrenees. Indeed, he discusses at some length in his book the evidence (or absence of it) which might answer the question "Did he come to the Pyrenees?".

"Daniel Defoe's text," Joseph Ribas writes, referring to the description in the novel of Crusoe's journey across the Pyrenees, "although brief and lacking in topographical details, contains several credible observations which hint at a real itinerary and which could lead us to believe that the writer made the journey himself."

Moreover, it is known that Defoe spent time in France and Spain in or around 1681 and 1682.

And Defoe has Crusoe insist on the veracity of the incidents in his story, for example in saying "the story of the bear in the tree and the fight with the wolves is likewise matter of real history..." . By implication, the route which Crusoe took over the mountains is "real".

But Joseph Ribas finally has to acknowledge that there is no proof that "Daniel Defoe actually crossed these mountains".

"Mais qu'importe!" (No matter!) he writes. "Robinson Crusoe has become such a flesh and blood character in our imaginations that he overshadows his creator. It is Crusoe who is with us and who walks at our side. We become the travelling companions of a hero of adventures."

In the realm of imagination

So now, under the guidance of Joseph Ribas, we can imagine, if we ever have the good fortune to be walking in the high Pyrenees mountains, that we can see Robinson Crusoe and his companions riding over the pass, heading north towards their fateful confrontation with a huge pack of ferocious wolves.

Furthermore, in his book, Joseph Ribas deploys his own imagination to enrich the story of Crusoe's journey from Pamplona to Toulouse - with tales of his own making and with descriptions of the landscapes crossed by the travellers. Joseph Ribas's additions are interwoven with a translation of Defoe's original text.

In Defoe's account of the adventures on the French side of the Pyrenees, we see Crusoe the hero, organising his men with military precision in the fight against the horde of famished wolves. But in Joseph Ribas's brief stories of Crusoe on the Spanish side, we see Crusoe as a more relaxed human being. As the travellers make their way across the warm plains of Aragon, for example, Crusoe admires the landscape and takes note of the charming and vivacious ladies who, he learns, are said to be the "most beautiful women in Spain".

Before that, in Pamplona, when Crusoe has to wait for snowstorms to pass before setting off, Joseph Ribas describes Crusoe in a festive mood. He enters an inn frequented by ladies and gentlemen of the town. At first he is treated as a guest of honour, and he is seated at a table laden with delicious food. Two young ladies serve him wine and cut slices of meat for him.

Crusoe gives way to the warm atmosphere of the place and becomes more than a little merry. He begins to sing and he gets up and tries to dance. But he just looks and sounds foolish. He makes gestures towards the ladies which cause them offence. His hosts decide they have had enough. Crusoe soon finds himself in the cold air outside the inn, with the door behind firmly closed.

Thus Crusoe is as fallible as any of us. He is no superman.

In particular, Crusoe's encounter with the wolves in the Pyrenees mountains leaves him profoundly shaken. For, as he relates near the very end of Defoe's novel, "I was never so sensible of danger in my life... I gave myself over for lost... and I believe I shall never care to cross those mountains again: I think I would much rather go a thousand leagues by sea, though I was sure to meet with a storm once a-week."

Robinson Crusoé dans les Pyrénées, by Joseph Ribas - published in France in 1995 by Éditions Loubatières (ISBN: 2-86266-235-6), with illustrations by Jean-Claude Pertuzé